Advisors have the option to use a trust fund company that does not compete against them. There will be an avalanche of asset transfers between generations over the next 30 years. This blog provides information on the past, present, and future of trust law and the trustee industry. This information will help advisors to make informed decisions on clients’ generational planning choices, and to attract and retain assets.

Introduction on Trust Law and Trustee Industry

A trust owns assets in trust for one or more beneficiaries that are administrated by a trustee. Over the past two decades the trust fund industry serving personal trusts has been changed forever. The evolution of the stodgy, roughly 700-year-old industry to the modern era stems from independent trust fund companies and several states modernizing their trust statutes (Holdsworth 1975, pp. 414–417). The large traditional trust fund companies have adapted by mimicking these smaller independent trust fund companies. With the rise of the internet, the democratization of information, and the interconnectivity of information, the trust fund company or corporate trustee serving personal trusts is at a unique junction. What remains the same is the common thread of trust and fear that weaves through a client’s everyday financial life. The changes revolve around the need for innovation and collaboration in our information and technology age and retaining the trust and personal touch of corporate trustee services. Financial advisors who provide generational planning need to understand the changes and opportunities in the trust fund industry. At stake, for financial advisors and their clients alike, is the dependable execution of those generational plans and the $24 trillion of future bequest transfers (after taxes and charitable giving) (Srinivas and Goradia 2015, p. 6). Capitalist societies continue to evolve. This includes the trust fund industry.

History of Trust Law

To know how trust law could evolve, it helps to know where it began. Trust law has existed for 2,000 years. The foundation of current U.S. trust law is from Roman and British law. The Roman Empire established the legal concept of a testamentary trust (created within a will). The signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 in England allowed the legal concept of individuals owning property and assets. The concept of a living trust (also known as a revocable trust) emerged due to the Crusades. Men left England to fight in the Crusades and re-titled their property in “trust” managed by a trusted individual should they not return home. In a series of cases from the early 1300s, the law responded to trustees not fulfilling their fiduciary duties by codifying trustee legal responsibility (Maitland 2010). The basic tenets of those court cases are represented in any trust statute that modern trustees are regulated to follow.

Basic Roles of a Trustee

A trustee has two key responsibilities: to provide for the distribution and the management of the trust assets. These responsibilities are described inside a trust document (testamentary, irrevocable, or living) that is essentially a contract between a trustee, beneficiary, and the creator (also known as the grantor or testator) of the trust. Over the past 20 years, there have been drastic changes in the trust industry (Maitland 2010).

Past and Present of the Trustee Industry

Our parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc. all had the same experiences with a trust fund company. The trust officer of a local or large bank offered trustee services to banking clients. Clients did not have easy access to knowledge nor choices about investments and trust law. Technology was limited to the speed of copier machines. Those trust officers’ duty was “to administer the trust solely in the interest of the beneficiary,”1 which began to be called the “sole interest rule.” The concepts of avoiding conflicts of interests, placing the needs of the beneficiary before the trustee, and other related fiduciary concepts were followed. There was no real leap of faith for families dealing with their trust officers at the local or large bank. Decisions were made locally. The trust officers lived locally. Those banks custodied the trust investment assets, which is why trust documents had large capital and surplus requirements. (As an aside, estate planning attorneys are beginning to recognize the custodial powerhouses such as Schwab, Pershing, Fidelity, and TD Ameritrade, to name a few, that make the large capital and surplus requirements for corporate trustees irrelevant today.) Independent financial advisors did not materially exist during this trust fund company golden period, so families enjoyed solid customer service from their trust officers at these banks. Clients of those banks felt comfortable having zero control over trust investments and distributions.

Financial services lurched into the modern era beginning on May 1, 1975.2 Known as May Day in the financial industry, on that date regulators removed fixed-rate stock commissions. Innovative and collaborative companies, such as Charles Schwab Corp., were founded and began to offer faster, cheaper, client-centric financial services from trading to custodial services. The democratization of information and the spread of information around technology platforms has only increased the trust that advisors and clients place on independent parties such as Charles Schwab. On the banking side, with the Douglas Amendment to the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 and a court case,3 banks were allowed to own banks in other states. This led to bank consolidations, which have continued to the present day. The effect on the “sole interest rule” was that decisions no longer were made locally. The trust officer at the large or regional bank trust company lost real decision power. Trust officer turnover began to grow at these banks. Trust committee decisions about distributions and investments began to be made far away in another state. Yet, the clients of these trust companies still placed their trust in these firms while having zero control. Local banks offering trust services, not swept up in the consolidation, continued to offer good old-fashioned trustee services. As the consolidations put earning pressure on the banks, which continues to this day, the loyalty to the beneficiary became blurry through many court cases.4 In the late 1980s and early 1990s, certain states, beginning with Delaware and followed shortly thereafter by Nevada and South Dakota, began to offer “modern” trust laws. These modern trust laws allowed the fiduciary risk and responsibility of trust investment and/or distribution decisions to be made by non trust fund companies. For example, financial advisors now could manage trust investments at the custodian of their choosing. These states also removed the law against perpetuities (i.e., trust not allowed to exist forever), and added privacy and asset protection laws. Their innovation and collaboration on trust law continues to this date.5 Also, by the mid-1980s, financial advisors began to leave the large national and regional brokerage firms and offer their services independently (O’Mara 2015). The consolidation of banks, founding of new custodians, and implementation of modern trust laws created an opportunity. Roughly, over the past two decades, we have seen the emergence of independent trust fund companies that are custodian neutral and choose not to compete against financial advisors. They are the trust fund industry innovators for clients and advisors (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Traditional and New Trust Fund Company Models

Picking a Trustee for a Trust Fund

Clients, estate attorneys, and advisors today have more choices than ever before on the type of trustee and the state governing law of a trust. The following sections describe the present ranges and outcomes of those choices.

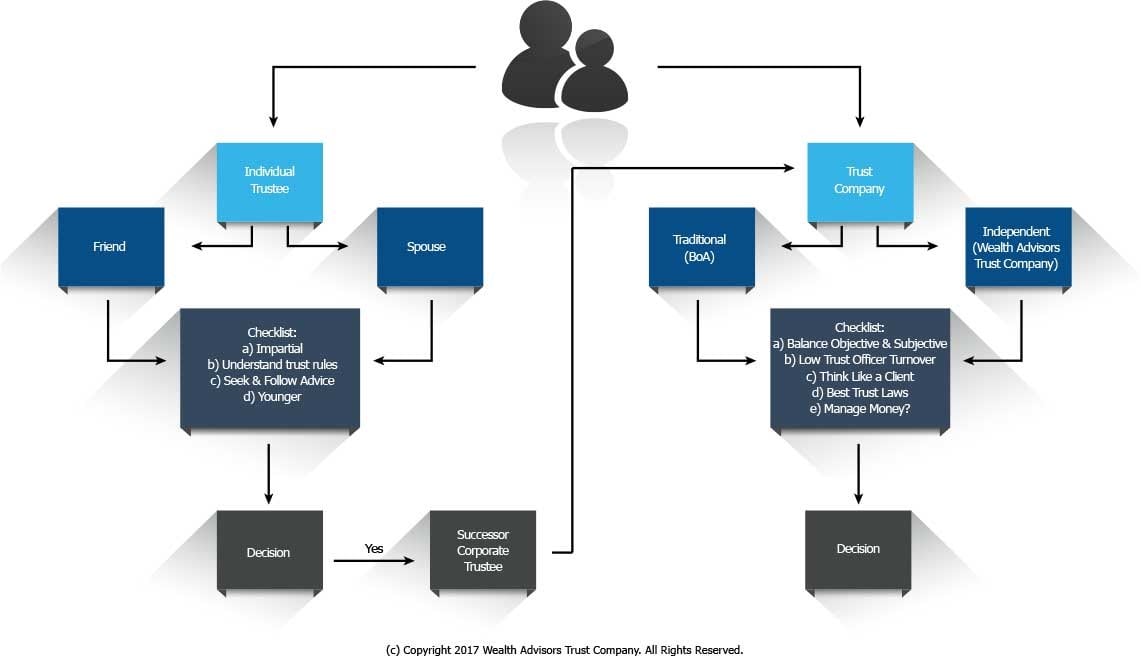

Picking a trustee generally gets less attention and time than choosing a new smartphone.6 In the first place, it is not a fun moment. When discussing the potential trustee choices for their trust, clients are sitting with an estate planning attorney or hopefully having the discussion with their financial advisor. Advisors see the whole financial picture and ask the questions about the “philosophy of a client’s money and their family.”7 For engineers and math people this is a logical process. For everyone else it is a winding road of emotions and what-ifs. To sum up, clients have to pick a few key roles in their wills or separate trusts. A trustee is one of those key roles (see figure 2).

Figure 2: PICKING A TRUSTEE

A client should consider an independent trustee (e.g., individual or corporate) when the beneficiary will have challenges with money, needs an impartial advocate, needs asset protection, or wants to keep the assets out of a future estate. Whatever the choice, all trust documents should allow for the trustee to be removed without cause, without filing with the courts, and allow the trust governing law to be changed based on the location of the successor trustee. Trustees should not have the ability to stymie change or remove the choices from a beneficiary.

The fiduciary needs and wants of beneficiaries, corporate trustees, and advisors can and must work collaboratively. Advisors and trust fund companies have the moral and legal fiduciary obligation to place their needs and wants second to the beneficiary; this is also known as the “sole interest rule.” A beneficiary’s fiduciary needs are very simple—distribution and investment decisions are made for their and future beneficiaries’ betterment. A beneficiary’s fiduciary wants are more subtle—keep me informed, make decisions quickly, don’t make me feel guilty when asking questions about distribution requests, and provide a collaborative experience with reasonable and customized responses and solutions. A trust fund company, acting as a fiduciary, is required to follow rules inside the trust document and have a clear process of who has the investment fiduciary risk and responsibility. Trustees, whether an individual or a company, want their services to have open communication between the advisor and the beneficiary. A trust fund company who accept that their services are A solution—not THE solution—will remain innovative, collaborative, and thinking always on the beneficiaries’ behalf. When a trust document delegates or directs for the use of an independent financial advisor, advisors want a seamless process. From the investment management to the mechanics of trust distributions, advisors want the trustee, whether an individual or a corporate trustee, to reduce and not add to their compliance concerns and daily workload. Advisors managing trust fund assets with an individual as the trustee are required, as a fiduciary, to be aware of the rules of the trust. Fiduciary roles and responsibilities around trust fund administration are paramount for advisors, so they need to use trustees who are well-schooled on these issues.

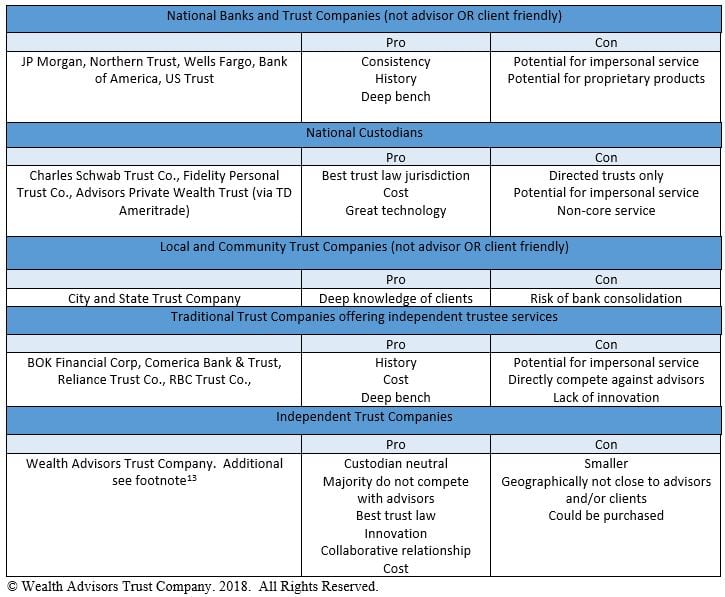

Advisors and clients are faced with multiple choices when choosing a corporate trustee (see table 1).

Table 1: ADVISOR AND CLIENT CHOICES ON A TRUST FUND COMPANY

Additionally, advisors can hire firms, such as National Advisors Trust, to private label trustee services under the name of the financial advisory firm.8 This brings a few extra complications and benefits. The benefits allow those advisory firms to show they offer a full suite of wealth management solutions including trustee services. The complications involve clients confused as to who is serving as the ultimate trustee (i.e., decision maker), higher regulatory scrutiny, and risk of the financial advisory firm unknowingly acting in a trustee capacity (e.g., approving trust distributions).

Setting aside that complicated solution, there is one last issue for advisors to consider. When choosing a trust fund company, advisors need to consider the following four key questions:

- Does the corporate trustee really understand the advisor’s business and clients?

- What legal and technological innovative solutions does the corporate trustee offer to make the advisor’s daily workflow and client experience better?

- Does the corporate trustee allow the advisor to choose the custodian and investment process?

- Apart from making a profit, why is the corporate trustee offering these services to advisors?

Present and Future of Trust Law

The present state of trust law in the United States has its roots in common law, which was adopted from England (Jay 1985). The establishment and maintenance of trust law has been left to individual states in the U.S. federal legal system per our founding fathers.9 Throughout the past century, with U.S. society more mobile, there have been strong calls from attorneys, judges, and beneficiaries to create a standard for trust laws that states could adopt or use as a basis for their own versions. The Uniform Trust Code10 (UTC) was established in 2000 and has been adopted by a large majority of states. However, several states such as Delaware, Nevada, and South Dakota believed the UTC was not vibrant enough and have created trust fund laws that are industry leading (Worthington and Merric 2017). The key areas separating the top trust states involve decanting laws, directed trusts, perpetual trusts, no state income or capital gains taxes, privacy laws, self-settled trusts, and community property trusts.11 What remains constant is the focus of all trustees on the “sole interest rule.” Clients now can choose, within their trust documents (testamentary, living, or irrevocable), the best trust jurisdiction or at the very least allow the governing law of their trust documents to be changed based on the location and administration of the trustee (individual or corporate). The top trust states desire to attract high-paying jobs, which ensures their continued thought leadership as well as a vibrant trust-industry community in those states pushing for cutting-edge trust law.12

Directed trusts

A trust law hallmark occurred in 1994 for present day clients, advisors, and attorneys with the passing of the directed trust law in Delaware.14 Before directed trust laws, trust fund companies had the option to delegate investment management of trust assets to an independent financial advisor. Directed trust laws allow for the distinct fiduciary separation of trustee duties from a corporate trustee. Six states offer recognized leading trust law statutes (Worthington and Merric 2017). Advisors and their clients now have access to all the top trust law states regardless of their residence. Advisors making use of the directed trust laws in Delaware, Nevada, or South Dakota have the flexibility to manage trust investment assets independent of trustee guidance or oversight. The advisor, and not the trust fund company, bears the fiduciary investment risk. This raises a legal issue: Should advisors be formally informed that they, and not the corporate trustee, have this fiduciary investment risk? Currently, few independent or even traditional trust fund companies offering independent trustee services have procedures in place to inform advisors of this fact.15 One popular opinion among corporate trustees, and not shared by this author, is that advisors are professionals and are aware, or should be aware, of the trust statutes governing a trust document. Advisors should understand the consequences of serving under a directed trust.

Delegated trusts

Formally known as discretionary trusts in the trust industry, delegated trusts are the majority of trusts in existence today. They generally state that the trustee may delegate to an outside advisor the investment of the trust assets. Traditional trust fund companies elect not to delegate this investment authority, keep the investment fees, and subsequently fire any current financial advisor when they are the successor trustee in a client’s will, or a revocable or irrevocable trust. Independent trust companies delegate that investment authority to the advisor but retain the fiduciary investment risk, as does the advisor. Advisors and clients have the option to decant, or modify, the trust document when changing to a state with leading trust laws. There are inconsistent risk management practices among advisor-friendly trust fund companies regarding how to monitor the investment actions of those advisors. Some independent trust fund companies limit the advisor to certain investment models. Other trust fund companies are selective about which advisors they will work with based on SEC background checks or the investment approach they use for clients. The corporate trustee has the final decision on those risk management processes and not the advisor.

Advisors who want the choice to invest the trust assets need to clearly understand their legal responsibility under a directed or a delegated trust. Advisors and their clients are looking for corporate trustees to provide easy-to-understand terms and conditions of their trustee services around the “sole interest rule.”16

Future of the Trustee Industry

Changes in the trust fund industry will center on time, technology, transparency, creativity, and demographics. What will remain the same is every trustee’s focus on the “sole interest rule.”

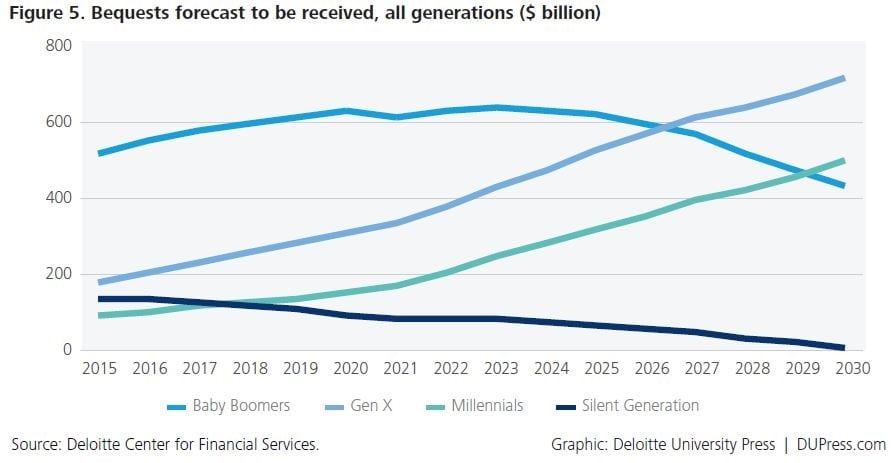

Demographic shifts in the United States are occurring in the general population and also in the advisor industry. Currently, 50 percent of advisors plan to retire within 14 years and yet only 66 percent of advisory practice owners have a succession plan in place.17 At the same time the transfer of wealth occurring between generations is titanic in nature. In 2015, the Deloitte Center for Financial Services provided a research report mapping trends of generational wealth in the United States (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Bequests forecasts to be received, all generations ($ billion)

It estimated that gen X and millennials will control almost 34 percent of all household financial assets by 2030 (Srinivas and Goradia 2015, p. 9). A general consensus of the financial industry is that the largest pools of those assets bequeathed to future generations will be in real estate, individual retirement accounts (IRAs), and trusts. Advisors focused on not being replaced by successor trustees (e.g., JP Morgan, Northern Trust, SunTrust, Wells Fargo, etc.) and beneficiaries of IRA accounts must address this issue with clients so the generational plans will remain consistent. There are two simple steps to accomplish this: (1) pick a few trust fund company that provides the trustee services that meet the goals of your clients and your business; and (2) review a client’s will and other estate-planning documents to suggest removing the traditional trust fund company and replace with an advisor-friendly trust fund company. At stake is the $24 trillion in bequests and who will retain, lose, or earn those clients. Advisory firms of all sizes are making strategic and tactical decisions about which trust fund companies to consider to use and when.

Time, technology, creativity, and transparency are the pivotal points for the future of the trust fund industry. Trust fund companies delivering on all these points in an easy-to-use, innovative, and collaborative process will gain the confidence of the advisor community. The majority of clients and advisors demand a perfect blend of user experience, technology, and human touch.18

For example, today, with a traditional corporate trustee, the process of a beneficiary requesting a trust distribution involves the following four steps:

- Beneficiary calls or emails trust officer explaining reason for distribution.

- Trust officer reviews request and sends to trust committee in another state.

- Trust committee reviews distribution request and approves, denies, or requires more information.

- Trust distribution made to beneficiary personal account.

Best practices involve collaboration and communication between advisors and trust officers. Today trust companies have automated the collection of the manual distribution request and communication between parties. The time between steps, communication gaps, and approving the distribution request has shrunk dramatically.

Another example is the administrative reviews all trust companies must perform on trusts. Currently this is a manual process of collecting information from trust transactions, required trust document actions, trust committee decisions, advisor notes, and beneficiary notes. In the near future, the collection and initial annual administrative review will be completed using machine learning. The back office of any trust company will shrink, and trust officers’ time on this manual process will almost disappear. Trust officers will have more time to solve issues in creative ways. Some trust companies and financial services companies' use of technology robs key employees of creativity but provides extra time that they will use on sales efforts versus more customized client service (McLean and Wolff-Mann 2018). That is a misaligned use of extra time given by technology. Also, trustee fees will become more transparent and initial quotes will be provided more quickly. All trustee fees are based on risk and time and can be broken down into the following seven factors:

- directed or delegated trust

- number of beneficiaries

- number of annual distributions

- number of trust(s)

- size of trust(s)

- type of trust assets

- custodian selection

Using algorithms and data across all trust accounts, corporate trustees will provide consistent and transparent trustee pricing based on those seven factors. As those factors change over time, a trustee will change its pricing. Today, advisors and clients generally choose a corporate trustee based on the trustee fee and state location. Tomorrow, users will demand that corporate trustees also provide services that are innovative, collaborative, and easy to use.

Time, technology, creativity, and transparency are the pivotal points for the future of the trust fund industry. Trust companies delivering on all these points in an easy to use, innovative, and collaborative process will gain the trust and confidence of the advisor community. The majority of clients and advisors demand a perfect blend of user experience, technology, and human touch.

For example, today with a traditional trust fund company the process of a beneficiary requesting a trust distribution involves the following four steps:

- Beneficiary calls or emails trust officer explaining reason for distribution

- Trust officer reviews requests and sends to trust committee in another state

- Trust committee reviews distribution request and approves, denies, or requires more information

- Trust distribution made to beneficiary personal account

Best practices involve collaboration and communication between advisors and trust officers. Today trust companies have automated the collection of the manual distribution request and communication between parties. The time between steps, communication gaps, and approving the distribution request has shrunk dramatically. Another example is the administrative reviews all trust companies perform on trust funds. Currently this is a manual process of collecting information from trust fund transactions, required trust document actions, trust committee decisions, advisor notes, and beneficiary notes. In the near future the collection and initial annual administrative review will be completed using machine learning. The back office of any trust company will shrink, and trust officers’ time on this manual process will almost disappear. Trust officers will now have more time to solve issues in creative ways. That takes time. That is a great use of time. Some trust companies and/or financial service companies will give in to the temptation of using this extra time differently. They will use technology to take away the creativity of their key employees so that extra time can be spent on sales. That is a misaligned use of extra time given by technology. The transparency of trust fund fees and providing a fast and accurate quote on those fees to advisors also will change for the benefit of everyone. All trust fund fees are based on risk and time. Those can be broken down into the following seven factors:

- directed or delegated trust

- number of beneficiaries

- number of annual distributions

- number of trust(s)

- size of trust(s)

- type of trust assets

- custodian selection

Using algorithms and data across all trust fund accounts, trust companies will provide consistent and transparent trustee pricing based on those seven factors. As those factors change over time, a trustee will change pricing. The future demand of advisors and clients on their choice of a corporate trustee will center around their prioritization of time, technology, creativity, and transparency.

Conclusion on Trust Law and Trustee Industry

This article has described the past, present, and importantly the future of trust law and the corporate trustee industry. Advisors and their clients have more control and choices with trusts than ever before. To summarize:

(1) advisors need to be aware of the consequences of serving under a directed trust;

(2) clients can use the best trust laws in the United States while living in another state;

(3) advisors can invest trust fund assets;

(4) advisors can be added into trust documents as only the financial advisor to provide multi-generational advice for their clients; and

(5) not all trust fund companies are truly advisor-friendly.

As much as the trust industry has changed and will continue to change, one tenet remains rock steady: The duty and responsibility to follow the “sole interest rule” for the beneficiary of a trust fund remains paramount.

Endnotes

[1]. Restatement (Second) of Trusts §170(1) 1959; accord UTC §802(a) 2000.

[2]. Id.

[3]. See Northeast Bancorp v. Board of Governors, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1984/84-363

[4]. See Ashby Henderson v. The Bank of New York Mellon, https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/massachusetts/madce/1:2015cv10599/167967/72.

[5]. Restatement (Second) of Trusts §170(1) 1959; accord UTC §802(a) 2000

[6]. Id.

[7]. Chuck Sharpe, Sharpe Law Group, personal communication (2018).

[8]. For example, National Advisors Trust Company, http://www.nationaladvisorstrust.com

[9]. Tenth Amendment of United States Constitution, Ratified December 15, 1791.

[10]. See http://uniformlaws.org/Act.aspx?title=Trust%20Code.

[11]. As of July 2018 only in Nevada, Alaska, and South Dakota.

[12]. Id.

[13]. See https://lp.thewealthadvisor.com/aftc_2018_lp.html

[14]. Directed Trust Statute, Delaware Code, Ann. 12 §3313.

[15]. Id.

[16]. 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, Financial Services Edition, https://www.edelman.com/

trust-in-financial-services-2018, p. 28.

[17]. State Street Global Advisors, The Advisor Retirement Wave, 2017; State Street Global, Prioritizing Succession Planning, 2017.

[18]. 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, Financial Services Edition, https://www.edelman.com/trust-in-financial-services-2018, p. 33.

Holdsworth, W. S. 1976. A History of English Law, Volume 4, Methuen: 414–417. https://books.google.com/books?id=PqE8oAEACAAJ.

Jay, Stewart. 1985. Origins of Federal Common Law: Part Two. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 133, no. 6 (July): 1,231–1,333.

Maitland, Frederic William (ed.). 2010. Bracton’s Note Book: A Collection of Cases Decided in the King’s Courts during the Reign of Henry the Third. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McLean, Bethany, and Ethan Wolff-Mann. 2018. Wells Fargo Automated High-Net-Worth Wealth Management as Advisors Faced Sales Pressure (July 18). https://finance.yahoo.com/news/wells-fargo-automated-high-net-worth-wealth-management-advisors-faced-sales-pressure-151535558.html.

O’Mara, Kelly. 2015. How Many RIAs Are There? No, Seriously, How Many? (November 11). https://riabiz.com/a/2015/11/11/how-many-rias-are-there-no-seriously-how-many.

Srinivas, Val, and Urval Goradia. 2015. The Future of Wealth in the United States (November 9). Deloitte Center for Financial Services: 6. https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/industry/investment-management/us-generational-wealth-trends.html.

Worthington, Daniel G., and Mark Merric. 2017. Which Trust Situs is Best in 2018. Trusts & Estates (December 13): 1.